Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI) completed multiple large thermoplastic composite (TPC) and liquid resin molded, out-of-autoclave (OOA) demonstrators from 2019-2023 and continues R&D to advance its expertise as a Tier 1 supplier for global high-rate production of next-generation single-aisle and eVTOL composite airframes. Source (All Images) | KAI

Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI) is the largest and most comprehensive aerospace manufacturer in South Korea. Headquartered in Sacheon, it was founded in 1999 through the merger of Samsung Aerospace, Daewoo Heavy Industries’ aerospace division and Hyundai Space and Aircraft Co. KAI designs, develops and manufactures military and commercial aircraft, provides aircraft maintenance and upgrade services and delivers aircraft components to Airbus, Boeing, Embraer, Bell Helicopter, Israel Aerospace Industries, Aernnova and Collins Aerospace. It also designs and builds unmanned aerial vehicles, satellites and space launch vehicle components.

KAI has steadily advanced its expertise, scaling to large composite primary structures with the T-50 supersonic fighter — co-developed with Lockheed Martin — including tails and control surfaces and the KUH Surion helicopter with >30% structure by weight, including composite tail boom and rotor blades. South Korea’s KF-21 Boramae fighter program marked KAI’s transition to independent composite design and analysis capability, including wings, tails and fuselage panels.

As part of global Airbus and Boeing supply chains, KAI developed automated fiber placement (AFP) and advanced autoclave cure for wing and fuselage assemblies. It also invested in resin transfer molding (RTM) and began research into other out-of-autoclave (OOA) processes as well as thermoplastic composites (TPC). The company continues to advance composites across its businesses, supported by state-of-the-art manufacturing and R&D facilities.

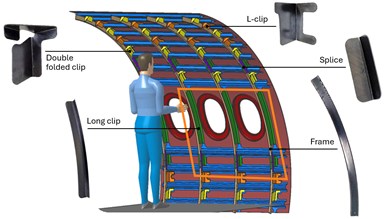

A key example is KAI’s 2019-2023 development of a 3-meter-tall, 2-meter-wide TPC fuselage section, including AFP skin, continuous compression molded (CCM) stringers, stamp formed clips and compression molded window frames from recycled materials, as well as assembly using induction and resistance welding. The company has also just revealed a 1.5-meter-long induction welded TPC wing control surface.

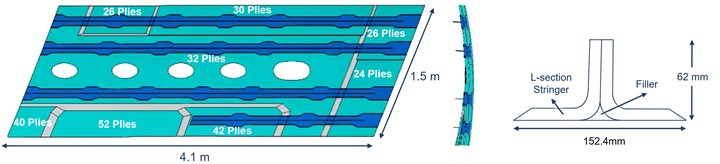

In a separate 2019-2023 program, KAI explored OOA structures including a 4.1 × 1.5-meter curved wing skin section with integrated stringers made with resin infusion plus torsion box demonstrators using infusion and same qualified RTM (SQRTM).

Reminiscent of Airbus-led, multi-partner programs such as the MFFD and Wing of Tomorrow, KAI has completed these developments to explore possible competitive advantages and technology maturity compared to conventional composites. “We have been supported by the Korean government to further develop our understanding, expertise and position as a Tier 1 supplier for higher-rate production of next-generation single-aisle aircraft and eVTOL airframe structures,” says Dr. Min Hwan Song, materials and process team leader at KAI.

TPC fuselage demonstrator

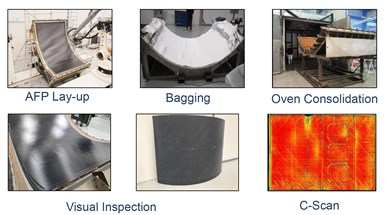

KAI’s TPC fuselage panel demonstrator began with fabrication of the skin using the process steps below.

“Our goal with this demonstrator was to prepare for the possible use of TPC structures in future aircraft,” says Song, “and broaden the range of options for OEMs.” To achieve this, KAI collaborated with Korean manufacturers, research institutes and universities, but also received assistance from the Royal Netherlands Aerospace Centre (NLR, Marknesse) and drew from the expertise of Toray Advanced Composites (TAC, Nijverdal, Netherlands) with its TC1225 carbon fiber prepreg made with LMPAEK polymer from Victrex (Clevelys, U.K.).

“We chose this material because it had a relatively lower processing temperature than PEEK and PEKK for producing primary structures,” says Haedong Lee, senior research engineer for TPC at KAI. “Due to the nature of TPC, higher processing temperatures make it more difficult to establish a process window. They also increase processing times and make it difficult to stabilize quality due to deterioration of auxiliary materials and thermal expansion of the mold.”

The program first developed a 1.3-meter-wide, 1.0-meter tall technical readiness part (TRP) with two stringers, three frames and two window frames to identify potential issues and establish process parameters prior to the final demonstrator production. Dimensions were selected based on available equipment and budget.

AFP skin + consolidation

AFP layup and consolidation of the fuselage skin were completed at NLR using its Coriolis Composites (Quéven, France) AFP machine and 0.25-inch-wide unidirectional (UD) tape. “We evaluated autoclave, oven and in situ consolidation,” says Song, “eliminating the latter due to its slow layup speed and high internal porosity that requires a heated mold to relieve thermal stress. To produce more industry-challenging and cost-competitive parts, we selected oven consolidation and achieved porosity levels equivalent or similar to the autoclave-consolidated samples.”

“Due to the high viscosity of thermoplastic resins, controlling internal voids during oven consolidation of the large 3 × 2-meter skin using only 1 bar of pressure in a VBO [vacuum bag only] process was the most challenging part,” notes Lee. “As skin thickness and size increased, so did the risk of voids.” To address this, KAI optimized the placement of bagging materials — specifically applying peel ply to the skin’s inner and outer mold line (IML, OML) — and stepped the layup edges during AFP to improve edge extraction of volatiles during consolidation.

KAI also used a two-step consolidation, completed in <7 hours. “Having a first dwell at 285°C allowed the preform/mold to reach thermal equilibrium,” says Song. “This induced uniform melting throughout the preform, reducing entrapped air before the final dwell at 355°C.” This consolidation cycle was recommended by TAC as were bagging materials including the following from Airtech International (Huntington Beach, Calif., U.S.): A8003G tacky tape, Release Ease 234 TFP peel ply, UHT Airweave style US7781 fiberglass breather and Thermalimide 50-micrometer-thick bagging film. A sheet aluminum caul was also used as well as Upilex heat-resistant polyamide release film from UBE Corp. (Tokyo, Japan).

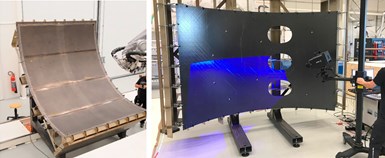

The TPC skin layup and consolidation mold comprised four pieces of Kovar welded together (left) while a metal framework was used to vertically position the completed skin for inspection using a structured blue light scanner (right).

For the layup and consolidation mold, KAI wanted to use Kovar, an iron-nickel-cobalt alloy with a very low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), similar to the iron-nickel alloy Invar. However, it was difficult to obtain large Kovar materials with the same surface area as the fuselage skin within the project schedule. “So, we obtained four pieces of Kovar and welded them together,” notes Lee. “There was a risk of vacuum leaks during oven consolidation at high temperatures, but with NLR’s technical support, we used the mold successfully without any major problems.”

That mold was designed to include compensation for deformation due to CTE differences between the mold and the part, as well as internal stresses during cooling. “This means the mold profile for layup and consolidation differs from that specified in the CAD,” says Lee, “and is unsuitable to use as an OML inspection tool to check for deformation in the finished part.”

Instead, KAI created a metal framework with the correct curvature and installed that on duck feet to enable inspection while standing the skin vertically. This prevented deformation in the flatwise curve of its surface due to gravity. A load of 4.5 kilograms per 300-millimeter interval was applied to the skin — a standard approach used for decades in the composites industry — to ensure contact with the inspection frame. A metrology scan of the IML surface using an ATOS 5 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) structured blue light scanner showed good results while a feeler gauge revealed near-zero gaps between the metal frame and OML surface.

The successfully finished skin featured a fast layup of 30 meters/minute, <1% porosity and sufficient crystallinity as evidenced via nondestructive inspection (NDI) and destructive tests, including DSC. “We confirmed AFP with oven consolidation as a viable alternative to the autoclave for thinner structures,” says Song. “However, autoclave consolidation offers the higher pressure required to reduce voids and porosity for thicker structures. For our fuselage skin, we applied 40 plies around the windows with good result, so we will continue to explore where this limit begins.”

CCM stringers

CCM works well for producing parts like stringers, says Song. However, the omega-shaped stringers for the final demonstrator required 12 plies with the stacking sequence [45, 0, -45, 90, 45, 0, 0, -45, 90, -45, 0, 45]. “This requires reprocessing the standard 0° rolls of UD material,” he explains, “cutting at +/- 45° and 90°, seam welding and then rewinding to create rolls for those orientations — demanding significant time and effort. If the material supplier could provide these as premade rolls, then CCM offers significant productivity advantages. However, its competitiveness remains uncertain, as the material is also expected to be significantly more expensive than conventional thermoset prepreg.”

To produce the twelve 1.9-meter-long stringers, KAI decided to avoid spending time on material preparation and instead used spot welding to make flat blanks from 12-inch-wide UD tape. These were then formed using a Teubert (Blumberg, Germany) CCM machine at the Korea Textile Development Institute (Daegu, South Korea).

Continuous compression molding (CCM) was used to produce twelve 1.9-meter-long stringers which would later be welded to the finished TPC skin.

Early on, cracks occurred through the thickness, says Lee, “due to inadequate temperature in the heating zone of the CCM press and insufficient crystallization.” The CCM equipment has a heating zone in the press area that performs heating, forming (while maintaining temperature) and cooling (solidification). “If the cooling rate is too fast,” he explains, “the thermoplastic resin cannot fully crystallize, and as forming pressure is applied to parts in the cooling zone, cracks may occur in the thickness direction. These issues were identified and addressed during production for the smaller TRP demonstrator. By optimizing the heating zone temperature, we were able to achieve 100% crystallization and eliminate the cracking in the final 1.9-meter stringers. We also achieved <1% porosity, near-constant thickness and accurate geometry thanks to including compensation in the tooling based on our analysis of deformation during forming and cooling.”

Stamp forming frames, clips

Depending on the size of the press, says Song, stamp forming is considered the most robust process for producing medium- to large-sized TPC parts (approximately ≈3 meters). KAI used its in-house R&D 1,000-kilonewton press with 500 × 500-millimeter plates to produce smaller clips sized 120 × 30 × 60-millimeters (L, W, H) and its 350-4,000-kilonewton Langzauner (Lambrechten, Austria) press with 2,000 × 1,000-millimeter plates to produce long clips (680 × 30 × 60 millimeters) and frames (1,200 × 50 × 60 millimeters).

UD TC1225 tape laminates held by tensioners in frames were preheated in an infrared oven and transferred by robot to the press. Initial TRP parts proved out deformation-compensated tooling while wrinkles during the press process were reduced by optimizing the laminates and tensioners, using forming analysis with AniForm software (AniForm Engineering, Enschede, Netherlands). Eventually, four 1.5-meter-long frames were produced for the final demonstrator, as well as more complex double-folded and L-clips, all with a fiber volume fraction (FVF) of 58-60%, sufficient crystallinity, constant thickness and <0.1% porosity.

“The most difficult part was developing the process for stamp forming the large, curved frames,” says Lee. “Each was manufactured in three parts to fit in the press and then assembled with fasteners into an integrated unit. But the typical quasi-isotropic laminate used for these can cause fiber wrinkles during stamp forming. In the past, we found it was necessary to use fiber steering during AFP layup, but in this project we were able to overcome this by optimizing the tensioning.”

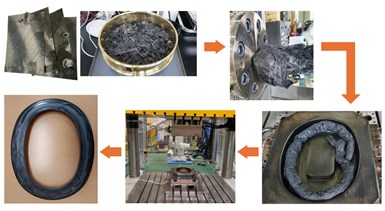

Compression molding recycled material

KAI wanted to explore using recycled scrap material and process waste to manufacture parts and so designed 600 × 450-millimeter window frames to demonstrate this in the fuselage module. Waste TC1225 UD material from manufacturing the skin, stringers, frames and clips was collected and shredded.

Waste from skin, stringers, frames and clips was shredded and sieved to ≈1-inch-length flakes, mixed with neat resin and extruded, then placed into a matched mold and compression molded into window frames.

“We wanted to use 1-inch-long fibers for higher mechanical properties,” says Lee, “and tried to regulate this during shredding, but there were still longer and shorter fibers. We used a strainer to obtain relatively uniform flakes and mixed in LMPAEK neat resin pellets at high temperature for enhanced formability.” The extruded mixture was then placed into a matched mold for compression molding.

“Even though the mixed material was relatively unevenly distributed within the mold, the high resin fraction enabled complete filling of the cavity,” notes Song. “Areas of lower resin fraction increased surface defects and decreased the spreadability of the fibers which caused a difference in the FVF within the product.” Still, KAI successfully molded parts with <0.1% porosity, 100% crystallization and an average 30% FVF.

Fuselage assembly

Assembly began with induction welding the stringers to the fuselage skin. KAI used a 10-kilowatt induction heating system from Ambrell (Rochester, N.Y., U.S.) integrated with an in-house robotic arm. “We initially worked with NLR to explore both fabric organosheet and UD tape,” notes Lee. “It was more challenging to design and optimize the induction coil for the tape.”

Assembly of the TPC demonstrator began with induction welding stringers (blue in diagram) to skin (top). The induction welding head (top right) used multiple rollers plus air cooling (blue pipe). Long clips were resistance welded to the skin while bonding was used for double-folded clips, L-clips and splice pieces.

“During welding, we applied pressure using a roller,” he continues, “but it was difficult to position it at the exact location in the induction-heated molten interface. We also used air to cool the composite surface adjacent to the induction coil, which tended to overheat. We achieved rapid heating and cooling at the induction weld interface, but the cooling prevented sufficient crystallization and resulted in deformation. To address this, we used heating cartridges in the welding mold tool to slow cooling.”

To assemble the frames, KAI used resistance welding to join the long clips to the skin while it bonded the small clips — double-folded clips, L-clips and splice pieces — to the fuselage skin and frames using an aerospace epoxy paste adhesive. The window frames were then attached using mechanical fasteners.

For both welding processes, KAI controlled temperature in the joint and surrounding laminate to achieve high-strength welds without material degradation. This included addressing edge effects and minimizing any unwelded areas. “For the stringers,” says Lee, “roughly 17 millimeters of the 25.4-millimeter width was induction welded and achieved a strength of 25 megapascals in single lap shear tests. Ultrasound C-scan results indicated low ultrasonic attenuation and good integrity in the welded joint.”

KAI has continued development. “Through improvements in how we apply pressure and other aspects,” says Lee, “we can now achieve weld strengths of 32-35 megapascals using induction welding without a susceptor or resin film.” He notes KAI has not yet attempted induction welding on structures with metal mesh lightning strike protection (LSP) already in the part. For this demonstrator, LSP was added after induction welding. “But this is something we’re working on,” says Lee, “and we are also exploring if induction welded assembly of recycled parts is possible by placing a carbon fabric on the outer layer of the molded part.”

Wing skin demonstrator

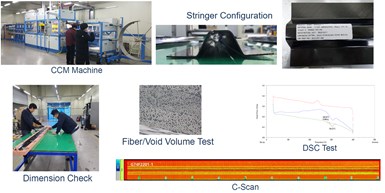

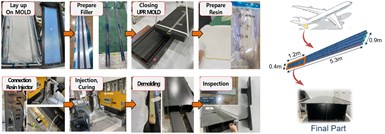

KAI’s second major program used liquid resin molding to produce wing skin and torsion box structures. Again, TRP research prototypes were used to identify potential defects and optimize process parameters. For the wing skin demonstrator, the 1.5 × 1.2-meter TRP was scaled to 4.1 × 1.5 meters with more complex geometry and curvature in the skin.

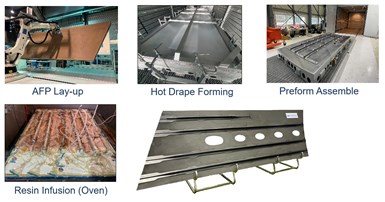

KAI’s wing skin module demonstrator used AFP layup

of dry fiber UD tape for skin and stringer blanks, hot drape forming for the L-stringer preforms and resin infusion of the assembled skin-stringer layup to produce the final integrated structure.

Instead of using noncrimp fabric (NCF), as has been demonstrated in the Wing of Tomorrow program, KAI used AFP with dry tape. “This enabled us to produce a competitive prototype, minimizing material loss compared to NCF preforms,” says Song. “For this demonstrator, we leveraged the wing shape of a 15.3-meter single-aisle aircraft main wing, selecting a representative section to capture key characteristics, including full skin stringers, shorter-than-skin stringers and inspection hatches.”

After evaluation and analysis, KAI chose HiTape UD tape and HexFlow RTM6-2 epoxy resin from Hexcel (Stamford, Conn., U.S.). AFP layup of 0.25-inch-wide tape was achieved at 0.6 meter/second. Stringers began as AFP blanks that were shaped into preforms using hot drape forming (HDF) equipment. “This system was developed through KAI’s tooling and fixture collaboration partners,” says Lee. “It is located inside an oven and uses a reusable silicone membrane, applying vacuum pressure once a specific oven temperature is reached.”

The stringers were preformed at 120°C for 15 minutes and then assembled with the AFP skin. “To ensure accurate stringer positioning, guide molds were placed at both the root and tip sections,” explains Song. “To establish the initial position of the shorter stringers, a separate fixture was fabricated and used in addition to the guide mold at the root section.”

In-oven resin infusion

The completed skin-stringer assembly was then vacuum bagged and prepared for infusion. “To overcome the issue of resin starvation,” notes Song, “it is crucial to establish the design and capacity for resin inlets and outlets and the overall infusion setup from the onset. Another key factor was the resin brake — length from the end of the maximum envelope of part [MEOP] without flow media — which controls the resin’s in-plane flow rate. Other key factors included the number of flow mesh layers used and the surface roughness of the mold tool, which both affect resin flow.”

Both infusion and cure were performed in an oven. “We did this to ensure uniform temperature distribution, because the resin viscosity is highly temperature-sensitive,” says Lee. “The resin feed lines used heat-resistant materials and incorporated a copper tube for enhanced thermal endurance.” A first 120-minute dwell was performed at 120±5℃ to ensure sufficient resin impregnation while the second at 180±5℃ achieved cure. No post-cure was performed.

The part was successful, enabling KAI to build expertise, comparing simulations to actual resin flow and process time and evaluating these versus OEM productivity requirements.

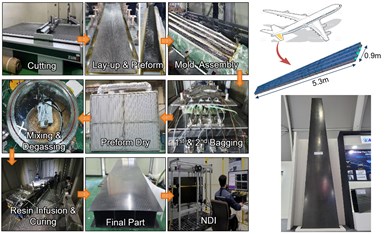

Torsion box using infusion, SQRTM

The next part of this program comprised fabricating two multi-spar torsion box demonstrators taken from the design of a large aircraft horizontal tail plane. Both comprised two skins and four spars (primary load stiffeners in the box versus stringers stiffening only the skin), one using resin infusion and the other SQRTM, which starts with a prepreg layup instead of a dry fiber preform and injects the same resin from the prepreg in a matched-mold RTM process. As explained in a 2010 CW article, “the resin isn’t intended to impregnate the prepreg, but only to maintain a steady hydrostatic pressure within the mold.” The result is a high-quality part that uses already-qualified aerospace materials.

“We were able to compare the results and evaluate the pros and cons of each process,” says Song. “We also optimized the torsion box shape, cost and lead time for each process, and gained practical experience regarding quality, production time and costs.”

Process steps for KAI’s resin-infused torsion box demonstrator included double bagging of the skin-spar laminate assembly and the company’s in-oven resin infusion process.

The resin-infused torsion box was 5.3 meters long, 0.9 meter wide and used QISO triaxial braided fabric from A&P Technology (Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.). “This selection began with a study of braided preforms and their characteristics,” says Seung-su Woo, senior research engineer for SQRTM at KAI. Due to hazmat shipping restrictions for one-component RTM 6 resin, KAI used the two-component HexFlow RTM6-2. Hexcel states that it has identical chemical composition and performance, but Woo notes RTM6-2 does require additional preconditioning, preheating and mixing.

Materials were cut and hand laid onto the mold tool. The wing spars were first preformed using HDF. The skin-spar assembly was then vacuum bagged. “One drawback of resin infusion is the high risk of leaks,” says Woo. “To overcome this, we used a technique called double bagging. We applied the normal vacuum bag materials and then bagging film for the primary vacuum bag. We then added breather materials and an additional layer of bagging film, which formed the second vacuum bag. Even if a leak occurred in the first bag, the second would maintain the vacuum pressure, effectively eliminating the risk of leaks.”

The double-bagged laminate was placed into the oven for resin infusion. RTM6-2 was degassed and injected into the dry preform with mold temperature at 95-100℃ and resin temperature at 90-95℃. Infusion was completed in 70-80 minutes and cure in 120 minutes at 180±5℃.

The structure was produced successfully and its quality verified with ultrasound C-scans as well as tests to validate glass transition temperature and degree of cure in the laminates. Dimensional checks using a laser tracker were performed on the skin and also for position, thickness and radius of the spars. Indeed, the most significant issue identified during testing was the spar radius geometry, specifically on the vacuum bag side, which exhibited inconsistencies, says Lee. “The conclusion was that this issue needs to be addressed through improvements to tooling or modifications to the manufacturing process.”

Steps for the torsion box demonstrator KAI produced using same qualified resin transfer molding (SQRTM).

The SQRTM torsion box was smaller, 1.2 meters long × 0.4 meter wide, to minimize cost for the matched-mold tooling required. KAI used Hexcel HexPly 8552 epoxy resin prepreg with plain weave carbon fiber and RTM equipment from Radius Engineering (Salt Lake City, Utah, U.S.) for resin injection in combination with KAI’s Langzauner press to apply consolidation pressure. Resin was injected at 104±°C and cured at 180±5°C in roughly 5 hours.

“We refined the process through production of TRP prototypes and were able to produce highly satisfactory results,” says Woo. “Even though we achieved a high-quality structure with resin infusion, we believe SQRTM or RTM are more suitable for these box structures because the matched molds result in more accurate geometries. Infusion’s single mold creates issues for accuracy in the bag-side part features. In the end, this work further advanced our in-house technical capabilities and expertise in OOA processes.”

Qualified materials, future production

KAI has received Korean airworthiness authority approval for the TC1225 material as well as the HiTape dry fiber UD tape and HexFlow RTM6-2 resin. “Those material allowables can be used for the development of domestic airframe components,” says Song. “However, depending on the structures, additional properties may need to be tested. For TPC in particular, a foundation has been laid for future applications in domestic autonomous aerial vehicles.”

“However, we believe that welding technologies require further research to attain the maturity of thermoset composite bonding processes (co-bond, co-cure, secondary bonding),” says Lee. “KAI is continuing to research induction, resistance and ultrasonic welding, and we also see molding of waste TPC materials as an environmentally friendly process. Although uneven fiber length and distribution risks parts with varying physical properties, with further development, we see significant potential for future applications in secondary structures.”

“We continue to focus on the development and production of airframe components for major OEM programs,” says Song. “Our goal is to support next-generation single-aisle production rates of 60-100 aircraft per month. These demonstrator projects have played a key role, helping us target the most competitive processes for high-quality complex composite structures and reduce takt time. As our customers request higher production volumes, we will build the infrastructure needed to meet those demands.”

Related Content

ASCEND program completion: Transforming the U.K.'s high-rate composites manufacturing capability

GKN Aerospace, McLaren Automotive and U.K. partners chart the final chapter of the 4-year, £39.6 million ASCEND program, which accomplished significant progress in high-rate production, Industry 4.0 and sustainable composites manufacturing.

Read MoreAutomated robotic NDT enhances capabilities for composites

Kineco Kaman Composites India uses a bespoke Fill Accubot ultrasonic testing system to boost inspection efficiency and productivity.

Read MoreEvolving natural fiber technology to meet industry sustainability needs

From flax fiber composite boats to RV exterior panels to a circularity model with partnerships in various end markets, Greenboats strives toward its biomaterials and sustainable composites vision in an ever-changing market.

Read MoreUpdate: THOR project for industrialized, recyclable thermoplastic composite tanks for hydrogen storage

A look into the tape/liner materials, LATW/recycling processes, design software and new equipment toward commercialization of Type 4.5 tanks.

Read MoreRead Next

Plant tour: Aernnova Composites, Toledo and Illescas, Spain

RTM and ATL/AFP high-rate production sites feature this composites and engineering leader’s continued push for excellence and innovation for future airframes.

Read MoreCombining multifunctional thermoplastic composites, additive manufacturing for next-gen airframe structures

The DOMMINIO project combines AFP with 3D printed gyroid cores, embedded SHM sensors and smart materials for induction-driven disassembly of parts at end of life.

Read MoreCeramic matrix composites: Faster, cheaper, higher temperature

New players proliferate, increasing CMC materials and manufacturing capacity, novel processes and automation to meet demand for higher part volumes and performance.

Read More