A duct for air handling may seem to be a straightforward component, but when that duct is part of the environmental control system on an aircraft, there are potentially a number of requirements it needs to meet.

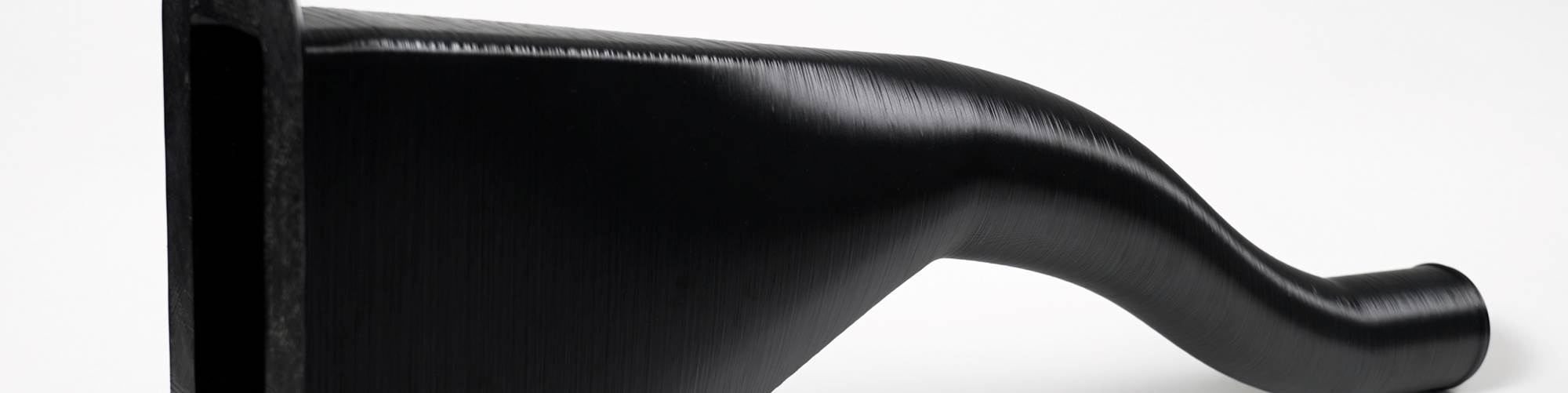

Eaton's early work on developing polymer composite ducts focused on blow molding, but that process would be challenged to produce a duct shape such as this featuring a drastic transition. This duct section is a little under 3 feet tall. Eaton is now using additive manufacturing to produce aircraft duct sections like this up to 6 feet tall.

“There’s a very extensive list,” says Si Chen, a senior specialist engineer with a focus on polymer nanocomposites who is part of the Advanced Materials and Processes Group with Eaton. “There is a V0 flame rating: A flame must be extinguished within 10 seconds on a vertical surface. There are things like chemical resistance, smoke and toxicity — in addition to application-specific requirements like vibration handling and the specific strength requirements of the part.” Another notable requirement is for duct material to be electrostatic dissipative (ESD). And all these needs must be satisfied for a part that is also apt to be geometrically complex enough to wend around and through other components of the aircraft. Formed aluminum has been the material of choice to make aircraft ductwork that meets all these needs, but Chen is part of a team at Eaton that has now realized a potentially faster, cheaper and more flexible method of manufacturing aircraft ducts. 3D printing in polymer composite offers a way to produce ducts on demand, without tooling and with greater design freedom.

Eaton engineer Si Chen lists the requirements a nanocomposite applied to aircraft ducts must meet. They include flame, chemical and vibration resistance, and the material must be electrostatic dissipative.

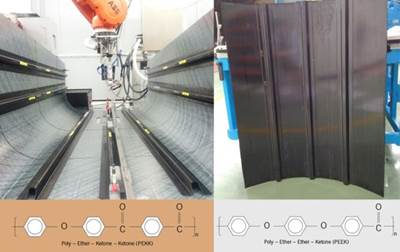

Key to this solution was developing a 3D printable material satisfying all the requirements of the aircraft application as well or better than aluminum. Eaton’s material, the product of development work performed over years, is a carbon-fiber-reinforced PEKK tailored to the ductwork role.

Javed Mapkar is senior technical manager of the same group at Eaton. The material is ready — proven within Eaton’s testing internally — and is now proceeding through third-party testing so it can be applied as a replacement for aluminum in aircraft production. That work is now being done through the National Institute for Aviation Research (NIAR) at Wichita State University. He says, “For this ESD PEKK material, we are trying to qualify it for B-basis allowables. We need to make multiple batches of the material, print on multiple different printers, and show repeatability.”

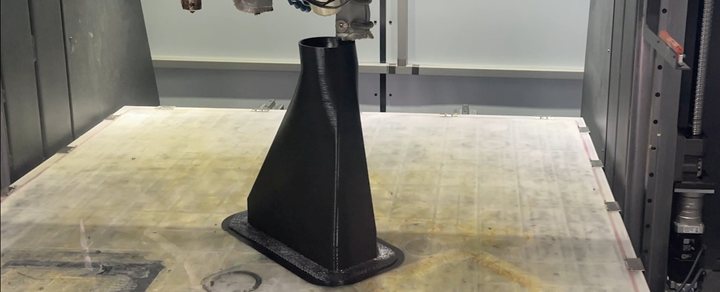

A pellet-fed 3D printing system has simplified material development, but it also provides the way to deliver enough material for unattended production of multiple large ducts at once.

The 3D Systems Titan 3D printer used at Eaton's Southfield, Michigan, site where the duct-related material and process development has been done. The machine is seen here with additive manufacturing engineer Jimmy Ward. The size of the machine allows for production builds of multiple large duct sections at once.

A 3D printing platform capable of using pellet material is part of this solution as well, and part of the process now being qualified. Material development was done on, and parts have been made on, a Titan pellet-fed extrusion 3D printer from 3D Systems. Eaton could have pursued a solution using material in the filament form more common to extrusion 3D printing, but getting to produce the material in pellet form simplified and sped material development. Pellet stock also offers the more practical way to deploy enough material for an unattended build of multiple large aircraft ducts. The Titan machine used, with a build volume of 50 × 50 × 72 inches, makes it possible to 3D print ducts up to 6 feet high in multiples of four to eight ducts per build — which is what production will ultimately entail.

Javed Mapkar, senior technical manager for Eaton, sees various possible paths once the PEKK material and AM process are qualified. A flexibile part production facility for ducts is one of these.

A production build like this might take on the order of 12 to 15 hours, Chen and Mapkar say, depending on the size and quantity of ducts. Importantly, the ducts could also be all different in this build. Aircraft production quantities are small enough, and duct designs in a plane varied enough, that duct manufacturing is inherently high-mix, low-volume production — yet ducts made of formed aluminum are beholden to hard tooling. The chance to do away with this tooling simplifies manufacturing and brings new freedom to design, and also makes it possible to develop, test and modify new designs quickly.

After qualification of the material and process, Mapkar says Eaton is considering various scenarios for how to bring this new option to aircraft makers. The company already has a precedent in the form of an additive manufacturing production facility for metal aircraft parts, so one possibility might be a toolingless factory similar to this metal part site for on-demand production 3D printed composite ducts.

More From This Author

Peter Zelinski reports on the advance of 3D printing for industrial production as editor-in-chief of Additive Manufacturing Media. Find his work in Additive Manufacturing magazine, in The BuildUp newsletter, and on The Cool Parts Show, which he co-hosts. SUBSCRIBE HERE

Related Content

Ceramic matrix composites: Faster, cheaper, higher temperature

New players proliferate, increasing CMC materials and manufacturing capacity, novel processes and automation to meet demand for higher part volumes and performance.

Read MorePlant tour: Airbus, Illescas, Spain

Airbus’ Illescas facility, featuring highly automated composites processes for the A350 lower wing cover and one-piece Section 19 fuselage barrels, works toward production ramp-ups and next-generation aircraft.

Read MoreCombining multifunctional thermoplastic composites, additive manufacturing for next-gen airframe structures

The DOMMINIO project combines AFP with 3D printed gyroid cores, embedded SHM sensors and smart materials for induction-driven disassembly of parts at end of life.

Read MoreActive core molding: A new way to make composite parts

Koridion expandable material is combined with induction-heated molds to make high-quality, complex-shaped parts in minutes with 40% less material and 90% less energy, unlocking new possibilities in design and production.

Read MoreRead Next

Aircraft Ducts 3D Printed in Composite Instead of Metal: The Cool Parts Show #68

Eaton’s new reinforced PEKK, tailored to aircraft applications, provides a cheaper and faster way to make ducts compared to formed aluminum.

Read MorePEEK or PEKK in future TPC aerostructures?

Which is better for in-situ consolidated thermoplastic composite primary structures? Materials play a part as to whether a one-step or two-step process will prevail.

Read MoreMore Affordable Suture Anchors 3D Printed from PEKK: The Cool Parts Show #60

Selective laser sintering (SLS) of polyether ketone ketone (PEKK) is being used to produce medical implants that are more cost effective and perform better than their conventional counterparts. We highlight fasteners known as suture anchors in this episode of The Cool Parts Show.

Read More