Development of ASTM standards for composites: An insider’s perspective

According to Dan Adams’ inside perspective, two elements determine whether a proposed test method for composite materials becomes an ASTM standard.

While many of you are aware of ASTM standards for testing composite materials, few are aware of how they’re developed, and why particular methods and procedures are selected for standardization. In this column, I’ll attempt to provide an insider’s perspective on ASTM standards development, having been an ASTM member for close to 20 years, an active developer of ASTM composite test methods and the current vice chair of ASTM’s Committee D30 on Composite Materials.

For starters, ASTM International has more than 30,000 volunteer members and publishes more than 12,000 standards. ASTM is organized into more than 140 technical committees, each of which develops and maintains standards within a particular focus area. The ASTM committee that is focused on standards for composite materials, Committee D30, or ASTM D30, was started in the mid 1960s — around the same time that carbon fiber became commercially available. Committee D30 meets twice a year, typically for one-and-a-half to two days. Meetings are often co-located with other composites-related meetings and conferences, such as Composite Materials Handbook (CMH-17) meetings and the American Society for Composites (Dayton, Ohio, U.S.), SAMPE (Diamond Bar, Calif., U.S.) and CAMX conferences. Additionally, some ASTM D30 meetings are held as part of the larger ASTM International Committee Week, allowing attendees to participate in other ASTM committees on topics of interest. If you will be attending one of these conferences where Committee D30 is also meeting, you are invited to attend.

The ASTM D30 committee consists of seven technical subcommittees, focusing on editorial and resource standards, constituent/precursor properties, lamina and laminate test methods, structural test methods, interlaminar properties, sandwich constructions and composites for civil structures. As a result, the majority of an ASTM D30 meeting consists of a series of one- to two-hour subcommittee meetings. There are also administrative and planning meetings as well as time for informal discussions and side meetings with other attendees, making the meetings of even greater value to attendees. Of the roughly 250 members of Committee D30, typically 30 to 50 attend each ASTM D30 meeting, representing the general composites industry, commercial testing laboratories, government laboratories and universities.

Considerable time at ASTM D30 meetings is devoted to existing test standards, as ASTM requires that all standards be reviewed and either updated or re-approved every five years. Currently, ASTM D30 has more than 90 standards to maintain, and therefore several existing standards are discussed at every meeting. While some are balloted for re-approval as-is, many are updated based on input received from users and for consistency among D30 standards. All voting associated with the development, revision and re-approval of standards is performed through online written balloting that occurs once or twice between meetings. As ASTM is a full consensus organization, ballot items must be agreed upon by all voters. Any issue or concern brought forward through a negative vote must either by resolved to the satisfaction of the voter or found to be not persuasive by the committee. While it’s common for an initial ballot on a new test method to receive multiple negative votes, it’s rare in Committee D30 for a ballot negative to be voted not persuasive.

It’s common to require two or three ballots before the standard is finally approved. As a result, the standardization process often takes multiple years.

Turning attention to standardizing new test methods: My experience and observations suggest that there are two important elements for success. The first is identifying a need for the proposed test method. In general, there are two categories of needs for proposed test methods. First, there’s the need to measure a new property that’s of interest for a new application of composites. For example, a flat-coupon crush test method has been proposed for measuring the energy absorption associated with crushing composite laminates. This type of test method, featured in CW’s September 2012 column, is of interest to both the automotive and aviation industries for use in designing composite structures that are required to provide energy absorption during crush loading. The second category of need is associated with improving or expanding upon existing test methods. As an example of an improved standard, the V-notched rail shear test, ASTM D70781, was developed to improve upon the existing ASTM D42552 two-rail shear test. The V-notched specimen in ASTM D7078 provides significant improvements in the uniformity of shear stress and eliminates the need for machined bolt holes in specimens.

An example of a proposed test method that expands upon existing test methods is the single cantilever beam (SCB) test for sandwich composites, which is currently in the standardization process. Similar to the existing ASTM D55283 double cantilever beam (DCB) test for solid laminated composites, the SCB test is used to measure the facture toughness associated with Mode I dominant crack growth. However, as discussed in my April 2020 column, the existing ASTM D5528 DCB test is for delamination growth in unidirectional composite laminates, whereas the proposed SCB test is for facesheet/core disbond growth in composite sandwich specimens.

The second element for success in new test method standardization is a person to “champion” the test method through the standardization process. The first task of the champion is to present the proposed test method to the appropriate ASTM D30 subcommittee. Upon receiving feedback and encouragement to proceed, a formal request, referred to as an ASTM work item, is drafted and submitted for approval by the subcommittee chairperson. Then the work begins on writing the test method document. Once an initial draft is completed, it is submitted for balloting at the subcommittee level. Although subcommittee balloting can take as few as one ballot cycle, it’s common to require two or three subcommittee ballots to address ballot negatives and comments. Balloting then moves to the main committee level, at which point all ASTM D30 members are asked to vote on the proposed standard. Once again, it’s common to require two or three ballots before the standard is finally approved. As a result, the standardization process often takes multiple years. The number of ballots and length of time required depends on the familiarity of the composites testing community with the proposed standard. In cases where the proposed test method is already in use in the composites community, perhaps as part of a material specification, the process may be shortened considerably. Currently, there are eight proposed standards that have officially been registered as work items in Committee D30 in various stages of development.

ASTM D30 welcomes new members to attend meetings and get involved in the activities I’ve described. More information on Committee D30 is available online at https://www.astm.org/COMMITTEE/D30.htm. Additionally, contact me at my email Dan@WyomingTestFixtures.com for any questions. I’m happy to provide additional information and welcome you to the committee.

References

1ASTM D7078/D7078 M-20, “Standard Test Method for Shear Properties of Composite Materials by the V-Notched Rail Shear Method,” ASTM International (W. Conshohocken, PA, US), 2020 (first issued in 2005).

2ASTM D4255/D4255M-15a, “Standard Test Method for In-Plane Shear Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials by the Rail Shear Method,” ASTM International (W. Conshohocken, PA, US), 2015 (first issued in 1983).

3ASTM D5528-13, “Standard Test Method for Mode I Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Unidirectional Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composites,” ASTM International (W. Conshohocken, PA, US), 2013 (first issued in 1994).

Related Content

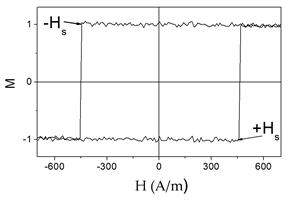

Glass-coated magnetic microwires for nondestructive composites monitoring

Glass-coated, amorphous microwires combine nanometer to micrometer diameters, enabling embedding into composites without degrading mechanical properties.

Read MoreNotched testing of sandwich composites: The sandwich open-hole flexure test

A second new test method has been standardized by ASTM for determining notch sensitivity of sandwich composites.

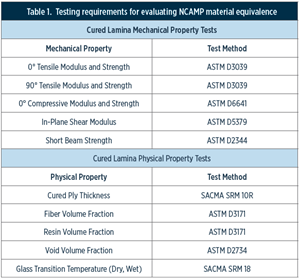

Read MoreMaterial equivalence testing in shared composites databases

In response to traditionally proprietary polymer matrix composites (PMC) qualifications, NCAMP continues its efforts to make material property databases publicly available.

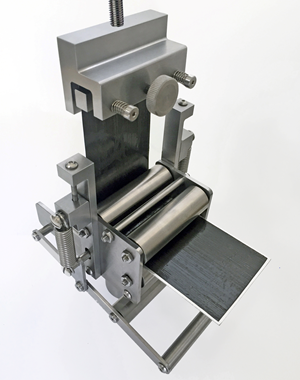

Read MoreComposite prepreg tack testing

A recently standardized prepreg tack test method has been developed for use in material selection, quality control and adjusting cure process parameters for automated layup processes.

Read MoreRead Next

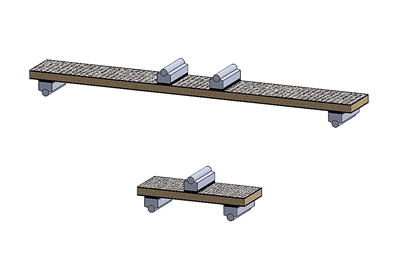

Flexure testing of sandwich composites

Dan Adams assesses the facesheet or core failures for three-point and four-points flexural loading configurations.

Read MoreCW’s 2024 Top Shops survey offers new approach to benchmarking

Respondents that complete the survey by April 30, 2024, have the chance to be recognized as an honoree.

Read MoreFrom the CW Archives: The tale of the thermoplastic cryotank

In 2006, guest columnist Bob Hartunian related the story of his efforts two decades prior, while at McDonnell Douglas, to develop a thermoplastic composite crytank for hydrogen storage. He learned a lot of lessons.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)