Jeff Sloan’s father-in-law, with his newborn daughter (Jeff’s wife to-be) and his 1966 Nassau blue Corvette Stingray. Source | CW

My father-in-law, in 1966, prior to the birth of his two children, purchased a new Corvette Stingray. I’ve never seen the car, but I’ve seen photos (like above). It was Nassau blue with a removable hardtop and much beloved by my father-in-law. After the birth of their first child — the person who would eventually become my wife — my father- and mother-in-law faced a dilemma: The Corvette was not designed to accommodate an infant in a car seat and thus was not a practical vehicle for a young family.

For this reason, my father-in-law made the difficult decision to sell the Corvette. However, as soon as the buyer of his Corvette drove away, my father-in-law regretted the decision to sell. In fact, he tried to buy the car back, to no avail. To this day, my father-in-law still gets sentimental any time the subject of conversation turns to his 1966 Nassau blue Corvette Stingray. It was the one that got away.

It’s been more than 50 years since my father-in-law made that purchase, and of course the Corvette, which debuted in 1953, has been through several iterations since . At 67 years old, the Corvette is one of the longest-living nameplates ever produced. Over that time, there have been eight generations of Corvette — designated C1-C8. The most recent generation is on the cover of this month’s CW.

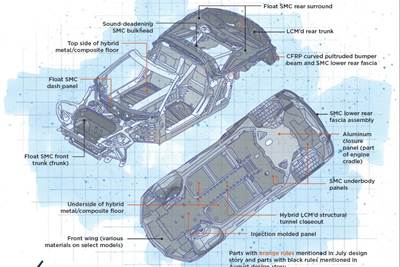

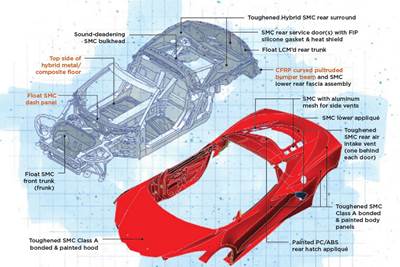

We split our coverage of the MY 2020 Corvette Stingray into two parts. Part 1 was published in July 2020 CW and Part 2 appears in this August 2020 issue, on p. 52. Both stories were written by CW contributing editor Peggy Malnati.

We had to divide our coverage over two issues because, frankly, the C8 generation is such a radical departure from the norm for the Corvette. If you are a Corvette aficionado, the most significant difference is that the engine in the C8 has been moved to the middle of the vehicle, which substantially changes the car’s lines and aesthetic. Indeed, as Peggy notes in her story, between the C7 and C8 generations, there is only one duplicate part. All else is new.

The second departure from the norm for the MY 2020 Corvette is its prolific use of composite materials. This is not to suggest that previous Corvettes lacked composite materials — you will recall that the Corvette was made famous, in part, originally by its use of fiberglass body panels. Indeed, throughout the Corvette’s life Chevrolet has proved most willing to apply glass and carbon fiber composite parts and structures to the vehicle. But even in light of this rich composites history, the C8 represents a step-change in composites use, ranging from the now famous curved composite rear bumper beam to the rear trunk and front trunk (frunk) to myriad underbody panels.

Possibly the most remarkable aspect of the MY 2020 Corvette is that it packs the new mid-engine concept into such a composites-intensive design to produce a vehicle that is — relatively speaking — so affordable. With a base price of $58,900, the Corvette is a veritable steal given its performance and engineering, and given the current market for high-end, high-performance, limited-production sports cars.

Despite all of this, and as appreciative the composites industry is of the Corvette and its place in composites manufacturing history, I can’t help feeling some disappointment as well — not in the car, but in the automotive industry. In the broader automotive universe, the Corvette continues to be the exception that proves the rule when it comes to composites use. I am reminded, every time I see a Corvette, that it is one of the few vehicles on the road that makes significant use of composite materials in major parts and structures, and remains affordable enough for most people to buy. Meanwhile, the rest of the mainstream automotive industry remains in the rearview mirror, making promising but definitely incremental use of composite materials.

Looking to the future, increased vehicle electrification does offer the composites industry a new opportunity to find applications well-suited for the materials. This is particularly true of applications, like battery covers, that don’t have a long history of using aluminum or steel and thus can be designed with composite materials and manufacturing processes in mind. It is in such applications that we should focus our energies.

In the meantime, I will continue to appreciate the Corvette for what was and what it has become. And I will see if I can’t track down the person who bought that 1966 Nassau blue Corvette from my father-in-law. Maybe he’s ready to sell.

Related Content

Cryo-compressed hydrogen, the best solution for storage and refueling stations?

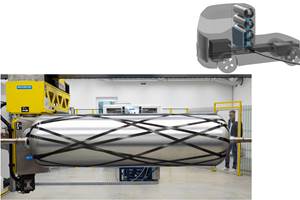

Cryomotive’s CRYOGAS solution claims the highest storage density, lowest refueling cost and widest operating range without H2 losses while using one-fifth the carbon fiber required in compressed gas tanks.

Read MoreNovel dry tape for liquid molded composites

MTorres seeks to enable next-gen aircraft and open new markets for composites with low-cost, high-permeability tapes and versatile, high-speed production lines.

Read MoreMaterials & Processes: Resin matrices for composites

The matrix binds the fiber reinforcement, gives the composite component its shape and determines its surface quality. A composite matrix may be a polymer, ceramic, metal or carbon. Here’s a guide to selection.

Read MorePlant tour: Joby Aviation, Marina, Calif., U.S.

As the advanced air mobility market begins to take shape, market leader Joby Aviation works to industrialize composites manufacturing for its first-generation, composites-intensive, all-electric air taxi.

Read MoreRead Next

Composites-intensive masterwork: 2020 Corvette, Part 1

Eighth-generation vehicle sports more composites, and features parts produced using unique materials and processes.

Read MoreComposites-intensive masterwork: 2020 Corvette, Part 2

Innovative composite materials trim mass, costs and noise on the high-volume mid-engine sports car.

Read MoreCW’s 2024 Top Shops survey offers new approach to benchmarking

Respondents that complete the survey by April 30, 2024, have the chance to be recognized as an honoree.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)