Testing is inefficient: Material simulation’s advantage over the status quo

Although simulation cannot replace validation and certification testing, it can offer a path to greater testing efficiency.

Historically, we have screened, characterized and designed new materials with physical testing because simple coupon tests are inexpensive and the results are generally accepted as fact, even when sample sizes are small. The problem is that material science has advanced: New materials are continuously evaluated for their potential, and choices need to be made between types of fibers, matrix materials, composite architectures, use of additional phases and effects of material defects. Further, the options available to support cost- and weight-saving innovations are now almost endless. A simple test matrix for screening alone can add up quickly and does not provide a lot of opportunity to evaluate sensitivities or explore large design spaces (see Fig. 1, at left).

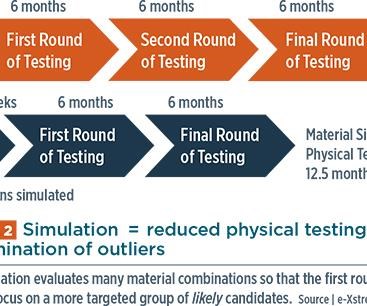

Test matrices are typically determined using engineering experience and internal methods (i.e., rule of mixtures). The time between ordering these tests and getting the results can easily be six months. With results in hand, decisions are made on how best to refine the test matrix for material down-selection. If results are promising, additional layups or material combinations are then ordered for a second round of testing. Another six months pass before results are ready for review. This process may be repeated once or twice before sufficient data are collected and a material is fully characterized (see below, illustrated in orange). Given today’s extraordinary number of possible material combinations, the conventional, multiple-step testing campaign described above, followed by validation and certification, has become extremely time-consuming and expensive.

Simulation tools can be used to accelerate this “test only” approach, addressing test process inefficiencies by quickly predicting the performance of a composite. They can make these predictions long before physical coupons could be ordered, let alone created, tested and analyzed. Simulations can cover several disciplines: mechanical and thermo-mechanical behavior, as well as thermal and electrical conductivity. Users of simulation tools also quickly discover that they can expand their design space and simulate many more combinations than they could physically test and, therefore, dig deeper into performance drivers. This additional material screening, characterization and design can be done in days or weeks, not months. Then, only the best candidates are selected for a shorter period (and fewer rounds) of physical testing (Fig. 2, at left, illustrated in dark blue).

For example, if we wish to optimize a material for stiffness and weight, material simulation can quickly determine the relationship of the composite’s stiffness and density to its fiber volume fraction and concentration of inclusions. Other properties are held constant between models, allowing us to compare and refine the variables we can control.

Rarely does anyone start from zero knowledge of their materials, so the inputs are either known or can be reasonably estimated.

The simulation results help to identify the material configurations for which we should invest in physical testing, thus eliminating a substantial portion of the original design space. Physical tests now can be focused on a more targeted group of candidates that feature combinations with a much greater probability of meeting design goals. The benefits here are two-fold: We can avoid testing combinations that clearly would have been outliers. Or, conversely, because it is now possible to conduct inexpensive virtual testing on additional candidates we might not otherwise consider, we can open doors that lead to greater materials innovation and a better understanding of the critical performance drivers.

Those who object to material simulation say users don’t have all of the constituent properties, and warn that fiber surface effects on composite performance and fiber/matrix interactions are difficult to predict. Others hesitate to use models that are not 100% predictive and insist on having a high degree of accuracy before using models in their material efforts. However, all of the challenges cited are analogous to the structural analysis of parts, where we have used finite element analysis (FEA) for more than 50 years. The only difference is that we are familiar with the assumptions that we need to make at the part level. With a little knowledge about our materials, simulation results can provide the same guidance and similar assistance with decisions that FEA does in structural parts analysis. That said, “garbage in” will be “garbage out”; therefore, when setting up our material models, we use caution to select input properties from known or trusted sources (e.g., NCAMP or CAMPUS databases) and, where possible, we crosscheck with hand calculations. Testing then can focus on validation and acceptance, not answering “what- if” questions that are easily addressed through simulation.

Anyone who remains uncomfortable with the original modeling assumptions can now reverse engineer properties from the test results. Tests are used to calibrate the models and then validate t he predictions. There are cases where the macro response of the material demonstrates a behavior that is caused by microstructural effects which are independent of the constituents’ physical properties. A simple rule of mixtures cannot account for these effects, nor does it give us the ability to modify orientations, include resin-rich areas or evaluate a filler’s dimensional effects on the macro performance. But physics-based models can include all of these effects and provide diagnostics at the micro-level, which would otherwise require complex test methods.

Calibrated models provide even more opportunity, either for further design or to augment the test results. Predictions of intermediate combinations give us more confidence going into the final round of testing. Certification is still done with physical tests, but now has the additional benefits of insight and optimization provided by simulation early in the process. At the end of the test campaign, the use of simulation has shortened the path to final acceptance.

A former professor of mine once said, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” If we accept that simulation is a useful guide for designing complex engineered systems, then we open up tools that can greatly accelerate new material design, development and insertion. Because we have well-established acceptance criteria for the products we manufacture and sell, we are ultimately interested in the final result and not the path we took to get there.

In summary, simulation doesn’t replace validation and certification testing, but offers a path to greater testing efficiency. Benefits include

- answers in hours vs. months.

- ability to inexpensively evaluate a much larger design space

- simple and inexpensive sensitivity studies.

- a deeper dive into what drives performance, which helps to focus test efforts.

Many companies hesitate to change the status quo, but those who do are using simulation to support material initiatives that are saving considerable time and achieving more optimal results than before.

Related Content

Materials & Processes: Resin matrices for composites

The matrix binds the fiber reinforcement, gives the composite component its shape and determines its surface quality. A composite matrix may be a polymer, ceramic, metal or carbon. Here’s a guide to selection.

Read MoreOne-piece, one-shot, 17-meter wing spar for high-rate aircraft manufacture

GKN Aerospace has spent the last five years developing materials strategies and resin transfer molding (RTM) for an aircraft trailing edge wing spar for the Airbus Wing of Tomorrow program.

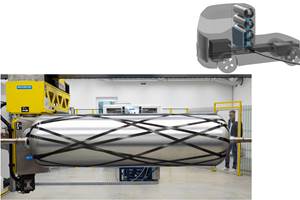

Read MoreCarbon fiber in pressure vessels for hydrogen

The emerging H2 economy drives tank development for aircraft, ships and gas transport.

Read MoreCryo-compressed hydrogen, the best solution for storage and refueling stations?

Cryomotive’s CRYOGAS solution claims the highest storage density, lowest refueling cost and widest operating range without H2 losses while using one-fifth the carbon fiber required in compressed gas tanks.

Read MoreRead Next

CW’s 2024 Top Shops survey offers new approach to benchmarking

Respondents that complete the survey by April 30, 2024, have the chance to be recognized as an honoree.

Read MoreFrom the CW Archives: The tale of the thermoplastic cryotank

In 2006, guest columnist Bob Hartunian related the story of his efforts two decades prior, while at McDonnell Douglas, to develop a thermoplastic composite crytank for hydrogen storage. He learned a lot of lessons.

Read MoreComposites end markets: Energy (2024)

Composites are used widely in oil/gas, wind and other renewable energy applications. Despite market challenges, growth potential and innovation for composites continue.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)