Market Outlook: Surplus in carbon fiber's future?

Participants at CW’s Carbon Fiber 2012 Conference see one coming as early as 2016.

One of the great attractions of CompositesWorld’s Carbon Fiber conference is the outlook on carbon fiber supply and demand, anchored each year by Chris Red, principal of Composites Forecasts and Consulting LLC (Mesa, Ariz.). Over the past few years at the conference, he has consistently forecast an imbalance in the carbon fiber market: Around 2016, carbon fiber demand will outstrip supply. Not so at Carbon Fiber 2012 (Dec. 4-6, La Jolla, Calif.). Crediting quick evolution and strong growth among carbon fiber manufacturers, Red predicted that the composites industry is in for several years of carbon fiber supply that exceeds demand.

What’s driving the trend to oversupply? There are several factors at work: new carbon fiber suppliers have entered the market; suppliers overall have increased the efficiency of their carbon fiber production; and, notably, there are signs of contraction in some markets — some are expected to consume less carbon fiber than initially anticipated.

That said, there is plenty of room for volatility, according to Red. A marked increase in the use of carbon fiber in the automotive sector, uncertainty in the market for wind turbine blades, new members in the formerly exclusive club of carbon fiber producers — some combination of these or other factors could unbalance the supply/demand equation yet again. As an example of one of those “other” factors, problems with a lithium-ion battery system has — as HPC went to press — grounded the fleet of Boeing 787 Dreamliners indefinitely, and although Boeing sees no effect on 787 production, industry observers differ. The bottom line is this is an exciting, if nerve-wracking, time to be a carbon fiber supplier and consumer.

The numbers

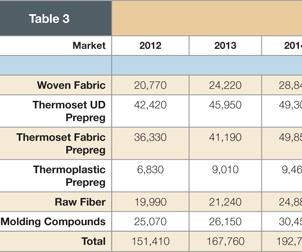

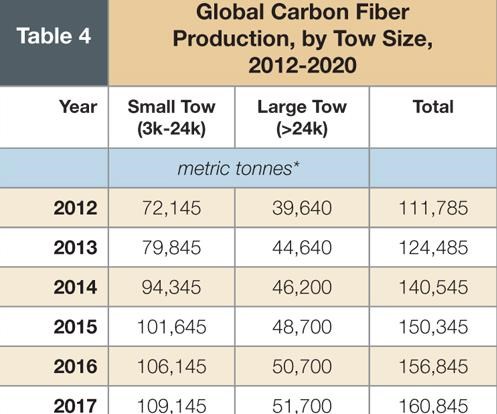

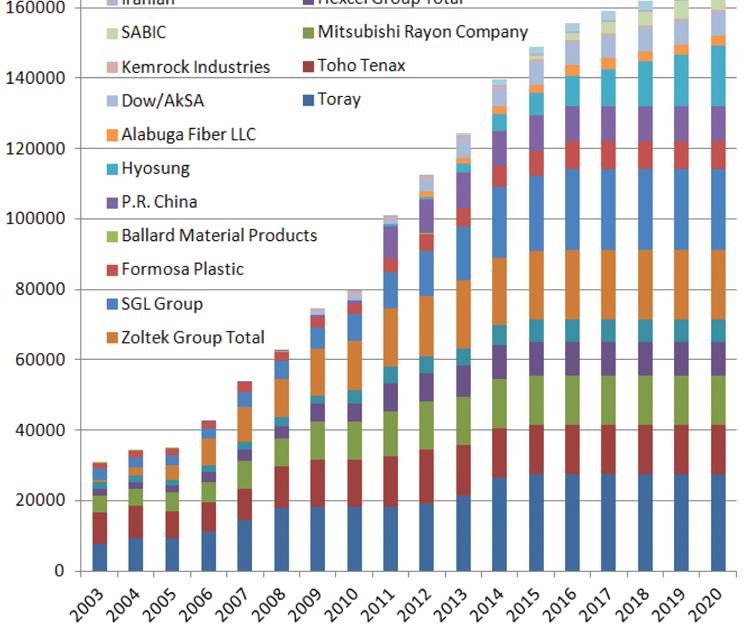

The charts, tables and graphs that accompany this story outline in detail Red’s carbon fiber forecast for the next few years. Here’s the big picture: In 2012, the global nameplate capacity of carbon fiber was 111,785 metric tonnes (more than 246.4 million lb), comprising 72,145 metric tonnes (>159.0 million lb) of small-tow fiber (3K to 24K) and 39,640 metric tonnes (>87.3 million lb) of large-tow fiber (>24K). By 2016, global nameplate capacity will rise to 156,845 metric tonnes (>345.7 million lb). Of that total, small tow will account for 106,145 metric tonnes (>233.0 million lb), and large tow, will account for 50,700 metric tonnes (>111.7 million lb). By 2020 (Red characterizes this as highly speculative), the global nameplate capacity will be 169,300 metric tonnes (>350.9 million lb). Small tow will make up 115,600 metric tonnes (>254.8 million lb);, and large tow, 53,700 metric tonnes (>118.3 million lb).

Tempering these figures is the caveat associated with any discussion about carbon fiber manufacture: knockdown. This is the difference between the nameplate capacity of a carbon fiber line and its actual production capacity. Actual output is always smaller due to inefficiencies in the manufacturing process. The good news is that Red expects manufacturing efficiency to increase substantially over the next decade. For 2012, he estimates efficiency was about 60 percent. By 2016, that number jumps to 68 percent, and by 2020, it could reach 72 percent. This means, of course, that a global nameplate capacity of 109,635 metric tonnes (> 241.7 million lb) in 2012 represents 65,781 metric tonnes (> 145 million lb) of actual carbon fiber.

On the demand side of the market, Red says the 2012 global carbon fiber demand in all markets was 47,220 metric tonnes (>104.1 million lb). By 2016, that number is expected to increase to 74,740 metric tonnes (>145 million lb) and then rise to 102,460 metric tonnes (>145 million lb) by 2020. Even with knockdown factored in, the 2016 demand will fall short of actual supply by about 25,000 metric tonnes (>145 million lb). And in 2020, the demand will fall short of actual supply by about 12,000 metric tonnes (>26.4 million lb).

Behind the numbers

The market forces that drive carbon fiber supply and demand are numerous and complicated, as Red quickly admits. It’s evident, however, that a few indicators, with little change, have the capacity to substantially shift the carbon fiber market.

Topping the list is the automotive market, which appears to be in the early stages of a long-term and substantial increase in the application of carbon fiber to structural and semistructural production vehicle components. Several presentations at Carbon Fiber 2012 touched on manufacturing processes that, with additional fine-tuning, could move carbon fiber into high-volume automotive manufacturing for mainstream cars. Red pointed in particular to the BMW i3 all-electric, four-door passenger car, due out later this year at an estimated volume of 30,000 units per year. It features a first-of-its-kind carbon fiber passenger cell, the fiber for which is supplied by a BMW/SGL partnership that has constructed a purpose-built carbon fiber plant in Moses Lake, Wash. (See “SGL Automotive Carbon Fibers plant’s two fiber lines in production,” under "Editor's Picks," at top right.) Red noted at the conference that the BMW i3 “application has significant potential to be as large as aerospace for carbon fiber, if not larger.”

Next on the indicator list is wind energy, where carbon fiber’s future is most uncertain. Carbon fiber is used primarily in large wind blades, and because this sector’s growth focused increasingly on offshore wind farms, it seemed — as recently as a year ago — that wind blade manufacturers would gobble up carbon fiber in runaway amounts. Red noted, however, that the recent expiration of the wind energy production tax credit (PTC) in the U.S., with its renewal the morning after for a mere year, and a Beijing-dictated ramp-down of wind energy expansion in China have put a damper on things. Still, Red estimates that the wind energy sector consumed 15,000 metric tonnes (33 million lb) of carbon fiber in 2012 and is on track to demand 23,440 metric tonnes (51.6 million lb) in 2016 and 36,840 metric tonnes (81.2 million lb) in 2020. This more moderate prediction, if fulfilled, will keep wind energy in the top spot, by far, as the largest carbon fiber consumer in the world. But the numbers will fall short of previous expectations. In 2010, Red predicted the wind energy carbon fiber consumption at 64,000 metric tonnes (141 million lb) by 2019.

A third indicator poses uncertainty for the carbon fiber market. Lockheed Martin’s F-35 Lightning II fighter jet features an all-composite skin, but it has suffered delays and cost overruns that are suppressing the orders outlook. “We’ll not see the annual unit production rates of even a few years ago,” Red suggested at the conference.

Making things interesting on the supply side is a host of new carbon fiber manufacturers, including Hyosung Corp. (pronounced “cho-sung,” Seoul, S. Korea), SABIC (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), DowAksa Ileri Kompozit Malzemeler Ltd. Sti (a joint venture of Dow Chemical Co., Midland, Mich., and AKSA, Istanbul, Turkey), Alabuga Fibre LLC (Moscow, Russia), Kemrock Industries & Exports Ltd. (Gujarat, India) and the government of Iran. All of these new supply sources provide (or will soon provide) industrial-grade (standard- and intermediate-modulus) fiber intended for use in markets other than aerospace. Applications of industrial-grade fiber (>24K) are growing at a faster rate than those for high-modulus, aerospace-grade (3K-12K) product.

New players are not expected to seriously challenge longtime producers in the short term. Toray Industries Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) is expected, throughout the forecast, to remain the largest carbon fiber supplier, but Red showed a cluster of other suppliers vying for second place, including Zoltek Corporation (St. Louis, Mo.), Toho Tenax Europe GmbH (Tokyo, Japan), Mitsubishi Rayon Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and SGL Carbon SE (Wiesbaden, Germany). And by 2016, Red estimates, the two largest carbon fiber producers will be Toray and SGL Group.

The confluence of new players and tempered demand has set up a likely surplus that will inevitably affect fiber pricing. “With this scenario,” said Red, “I would think that, unless the market grows significantly faster than I have projected, this excess capacity will keep overall pricing very competitive and may force a shakedown of the supply chain. Wind energy obviously is a big contributor to near-term issues, and the current subsidy policies are creating artificial booms and busts in the system, in both the U.S. and China.”

Price and precursor

Fiber pricing was a hot topic at Carbon Fiber 2012. Conference participants considered whether the industry can ever achieve the mythic $5/lb threshold that some would-be consumers of carbon fiber — among them, carmakers still reluctant to use carbon fiber in structural applications — claim would open up a variety of new applications.

For several years the belief has been that the industry can and should develop a less-expensive alternative to polyacrylonitrile (PAN) precursor, which makes carbon fiber notoriously expensive. Find a cheaper precursor, the thinking goes, and cheaper carbon fiber will result. Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL, Oak Ridge, Tenn.) has been studying alternate precursors for years. Although lignin was a possibility, the lab now is looking at polyolefin with partners Dow Chemical and Ford Motor Co. (Dearborn, Mich.).

Some carbon fiber manufacturers at the conference expressed skepticism that a non-PAN material can provide the same chemistry that makes carbon fiber so effective — particularly high-modulus carbon fiber for use in high-performance applications. But speaker Jai Venkatesan, Dow’s director of materials science and engineering, admitted that a year ago he, too, was pessimistic about the potential of polyolefin as a viable precursor. “However, we are confident now that we can turn the right knobs to spin the polyolefins in the right way. We think that this is possible.” He added that Dow estimates the carbon fiber yield from polyolefins, like polyethylene and polypropylene, might approach 86 percent.

Although it is by no means clear if this could result in $5/lb carbon fiber, a non-PAN precursor could certainly lead, at some point, to the manufacture of less-expensive fiber. Ross Kozarsky, senior analyst at Lux Research Inc. (Boston, Mass.), reported that his research indicates non-PAN materials do have a future as a precursor, but production of fibers from them would require innovations in oxidization and carbonization during the carbon fiber manufacturing process and would benefit only those who make standard- and intermediate-modulus fiber.

“I do not think high-modulus carbon fiber is a candidate for the alternative precursor work,” Kozarsky said, pointing out that “this work is driven by the ability to sacrifice performance for cost reduction.” That’s a tradeoff automakers can make because they have less stringent performance requirements. But it’s not an option in the aerospace market. “Applications that require high-modulus fiber are not a good opportunity for applying the alternative precursors.” Kozarsky also noted that current precursor efforts are focused on textile-grade PAN, which is less expensive. He said that ORNL/Dow and SGL Group, through FISIPE SA, the Barreiro, Portugal-based precursor manufacturer it recently acquired, are on this path. Kozarsky believes ORNL’s textile-grade PAN-based carbon fiber line will come online in 2013 and achieve carbon fiber unit costs of about $19.30/kg ($11/kg = $5/lb). This will lead, by 2016, to development of precursor based on melt-spun PAN and carbon fiber prices of $15.90/kg. By 2017, he said, assuming advances on the oxidization and carbonization side, expect a polyolefin-based PAN and carbon fiber price potential of $10.50/kg — below the $11/kg threshold.

“None of these innovations, taken alone, can reduce the cost enough,” Kozarsky warned. “It must be a combination of technology and innovation.” Further, a new precursor might change the chemistry of the resulting fiber. “Maintaining compatibility between the carbon fiber and the resin matrix will be critical.”

The carbon fiber manufacturing industry is already segregating itself by end market, with standard- and intermediate-modulus fiber designated for industrial markets and high-modulus fiber designated for aerospace markets. The development of a non-PAN precursor would insert itself into this split and become associated, by virtue of chemistry and function, with carbon fiber in industrial market applications.

Markets, applications, opportunities

The commercial aerospace market remains the most critical and highest profile application of high-modulus carbon fiber. With the Boeing 787 on the market and the Airbus A350 XWB in assembly and undergoing preparations for flight testing, it appears that the carbon fiber supply chain is headed into a period of stability. However, aerospace development outside the Boeing/Airbus spotlight, and possible new Boeing/Airbus projects, signal a dynamic marketplace.

Commercial aircraft orders are on the rebound, Red noted, after they peaked in 2007 at 3,487 and bottomed out at 663 during the recession in 2009. Boeing and Airbus reported strong sales in 2012 (Boeing had 1,203 orders; Airbus had 914) and healthy backlogs through 2018. Red estimates that commercial composite aerostructures were about 9.4 million lb (4,264 metric tonnes) in 2011 and 10.4 million lb (4,717 metric tonnes) in 2012. Of this, carbon fiber composites accounted for about 85 percent. About 35 percent of composite aerostructures are manufactured using automation, Red estimates. That number is expected to increase to 83 percent by 2020.

Beyond the 787 and A350, notable composite aerostructures in the works include the wing, empennage and flight-control surfaces on single-aisle commercial aircraft: the Bombardier CSeries, the Irkut MS-21 and the COMAC C919. On the military side, carbon fiber is key to the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II fighter, the Airbus A400M airlifter, the Embraer C-390 transport, the Eurofighter EF-2000 and the Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk unmanned aerial system.

The big question at every Carbon Fiber conference over the past few years has been whether or not carbon fiber composites will win a place on the fuselage of the next-generation single-aisle aircraft that will replace the Boeing 737 and the Airbus A320. The answer is maybe. Speaker Peter Zimm, principal of aviation consultancy ICF SH&E (Fairfax, Va.), noted that carbon fiber makes good sense in aircraft wings and many fuselages, but the skin thickness of a single-aisle craft, coupled with fiber placement laydown rates, makes aluminum a competitive option. Zimm says aluminum still makes up 48 percent of aerospace raw material demand, although buy weight is still a factor — the buy-to-fly ratio of carbon fiber is highly favorable. Although next-generation single-aisle aircraft from Boeing and Airbus are still on the drawing board, engineers at both companies are already monitoring the carbon fiber industry, looking for the advancements in material and process capabilities necessary to tip them toward composites.

Returning to solid ground, the next big thing in the carbon fiber industry is the automotive end-market. All eyes, for the moment, are fixed on the BMW i3, which represents a paradigm shift for composites use in a production vehicle and may prove to be a bellwether for other carmakers as they contemplate a similar use of carbon fiber.

However the automotive industry evolves, what’s clear is that the manufacture of carbon fiber automotive structures will require a robust, high-speed process that, even if it can’t mimic metal stamping, must provide cycle times of just a few minutes.

Several presenters emphasized such advancements. Globe Machine Manufacturing Co. (Tacoma, Wash.) was an attention grabber. Ron Jacobson, corporate projects manager, and Lloyd Champion, director, aerospace and industrial sectors, reported on Globe’s work with Plasan Carbon Composites (Bennington, Vt.) to develop an out-of-autoclave, high-speed, single-tool pressure press for the manufacture of Class A carbon fiber composite automotive parts. The machine, which features an enclosed and sealed processing chamber, offers a 17-minute part-to-part cycle time, 0 to 350 psi, 80 psi/min ramp rate, 110°F to 660°F (43°C to 288°C) direct heating, 900°F/482°C indirect heating, 28 inches mercury of vacuum pressure and the ability to accommodate a variety of part types and sizes, depending on the chamber size and shape. Jacobson emphasized that the machine is neither a compression molding device nor an autoclave (see "Faster cycle, better surface: Out of the autoclave," under "Editor's Picks," at top right).

Plasan uses the machines to mold parts for the 2014 Corvette Stingray at its facility in Walker, Mich. HPC learned that after the carbon fiber prepreg is laid up on the tool, it is covered and sealed with a reusable silicone “canopy” about 0.5 inch/12.7 mm thick. After the tool is loaded into the sealed chamber in the Globe press, pressure is provided by a pressurized air mass (<150 psi) that surrounds the tool and compacts the prepreg while it is heated by the tool.

Jacobson and Champion say the machine can process autoclave or out-of-autoclave thermosets, has applicability to aerospace manufacturing and could be used to process thermoplastics as well. Globe is testing aerospace parts in 2013 and hopes to receive an OEM process procedure approval for aerospace use sometime in early 2014.

Tapping a similar vein was Dale Brosius, president, Quickstep Holdings Ltd. (Dayton, Ohio), who reviewed his company’s automated through-thickness infusion and rapid-cure process. It uses resin spray transmission (RST) in a process that, Brosius says, approximates semipreg. In RST, the user starts with an open, empty mold. The mold is sprayed with a thermoset resin. A carbon fiber fabric preform is placed over the sprayed mold surface. The mold is then closed and the part is cured. The system, says Brosius, offers rapid heating and cooling (30°C to 40°C/min), 10-minute part-to-part cycle time, low tooling costs, energy efficiency, easy automation and parts with Class A surfaces. The material costs are said to be 20 to 40 percent less than prepreg, and parts can be either painted or clearcoated. Quickstep is selling and licensing the technology globally and, Brosius added, has placed a machine that, at HPC press time, is set to begin operation in the first quarter of this year.

Exhibitor Dieffenbacher North America Inc. (Windsor, Ontario, Canada) introduced its high-pressure resin transfer molding (HP-RTM) process, aimed at manufacturing automotive carbon fiber composites. Dieffenbacher officials at the conference said the company has developed machinery to automate fabric preforming, molding and finishing. Molding is performed at pressures of 80 to 100 bar (1,160 to 1,450 psi) and offers part-to-part cycle times of about three minutes. The process, said Dieffenbacher, is being used by a European automotive OEM to manufacture B-pillar structures for a production vehicle.

Next year, Tennessee

Other presentations at the conference covered a comparison of metallic and composite wings, design and engineering of large antenna structures, carbon fiber use in electricity transmission lines, automated dry fiber placement and design of reinforcements for damage tolerance. Check online at www.compositesworld.com for exclusive reports on these presentations.

Carbon Fiber 2013 has already been scheduled for Dec. 9-12 in Knoxville, Tenn., and will include a tour of Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Visit www.compositesworld.com and click “Conferences” for more information and to register for an e-mail service that will provide updates on the event.

Related Content

Novel dry tape for liquid molded composites

MTorres seeks to enable next-gen aircraft and open new markets for composites with low-cost, high-permeability tapes and versatile, high-speed production lines.

Read MoreMaterials & Processes: Fabrication methods

There are numerous methods for fabricating composite components. Selection of a method for a particular part, therefore, will depend on the materials, the part design and end-use or application. Here's a guide to selection.

Read MoreMaterials & Processes: Fibers for composites

The structural properties of composite materials are derived primarily from the fiber reinforcement. Fiber types, their manufacture, their uses and the end-market applications in which they find most use are described.

Read MoreInfinite Composites: Type V tanks for space, hydrogen, automotive and more

After a decade of proving its linerless, weight-saving composite tanks with NASA and more than 30 aerospace companies, this CryoSphere pioneer is scaling for growth in commercial space and sustainable transportation on Earth.

Read MoreRead Next

Faster cycle, better surface: Out of the autoclave

GM is first automaker to use Class A CFRP parts from new pressure-press technology.

Read MoreCW’s 2024 Top Shops survey offers new approach to benchmarking

Respondents that complete the survey by April 30, 2024, have the chance to be recognized as an honoree.

Read MoreComposites end markets: Energy (2024)

Composites are used widely in oil/gas, wind and other renewable energy applications. Despite market challenges, growth potential and innovation for composites continue.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)